Burma is a place that feels like a third world country, because it is. I went there during the hot season, March and April, 90-100 degrees and humid in the day. The landscape is typically dusty and brown. The tropical sun is blinding as usual.

In the cities the wide main throughfares are well-maintained, but the side roads are broken and gravelly or dusty and rocky. The more interesting roads are cluttered with street vendors, pedestrians, honking cars and motorcycles trying to bully their way through the crowds, and lined with restaurants and shops in big open garage-like spaces or under bamboo roofs, walls optional.

In the bright wet heat open shade is preferable to the indoors. Most Burmese cannot afford air conditioning—or the expensive power regulators to prevent them from being fried by the poorly maintained electrical grid, if there even is an electrical grid. This electricity is sometimes rationed. So is the water. The fancier places run their own generators and wells and septic tanks. In the poorer areas people count themselves content with have four walls and a roof. Some have no walls and a roof.

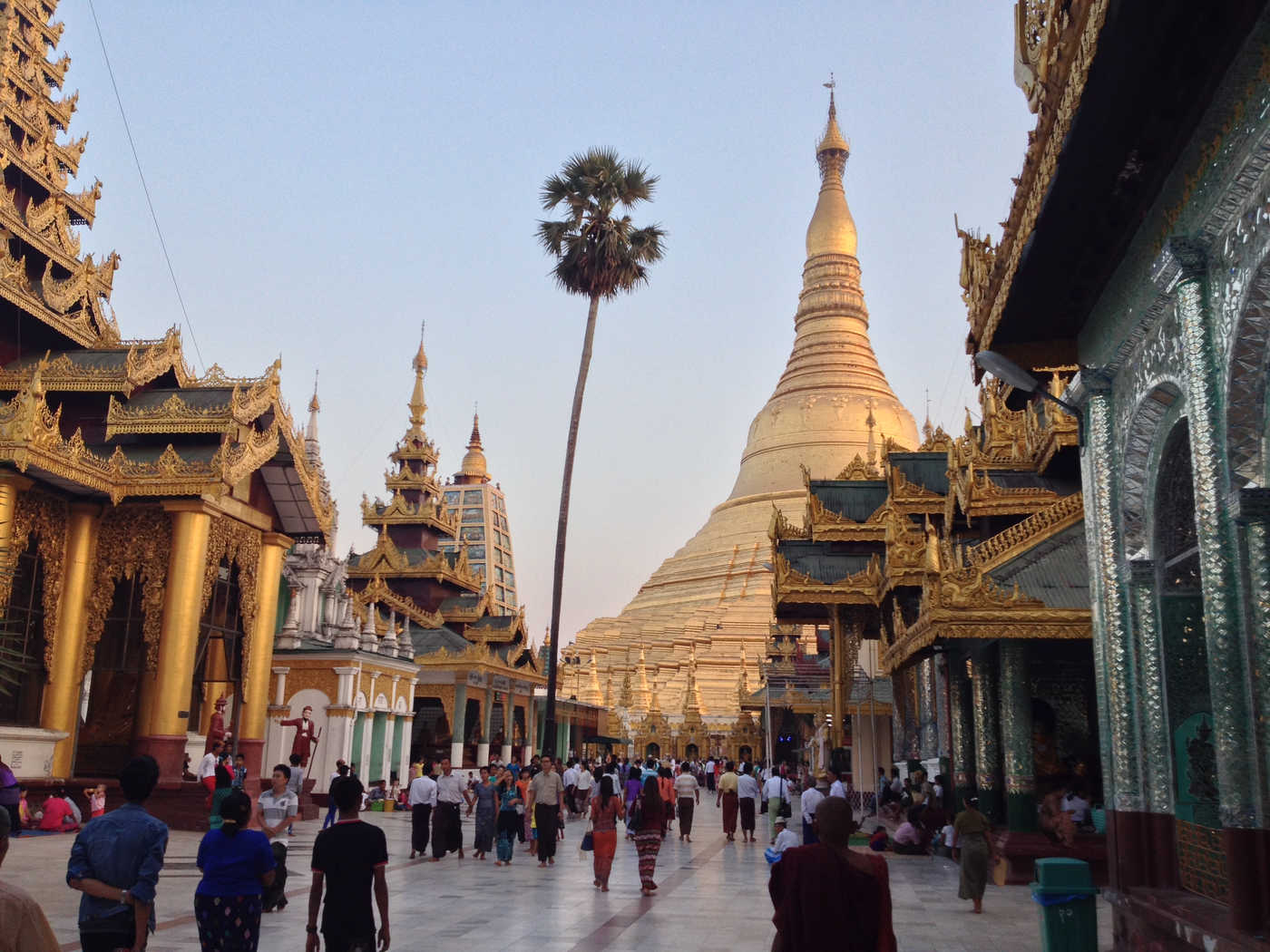

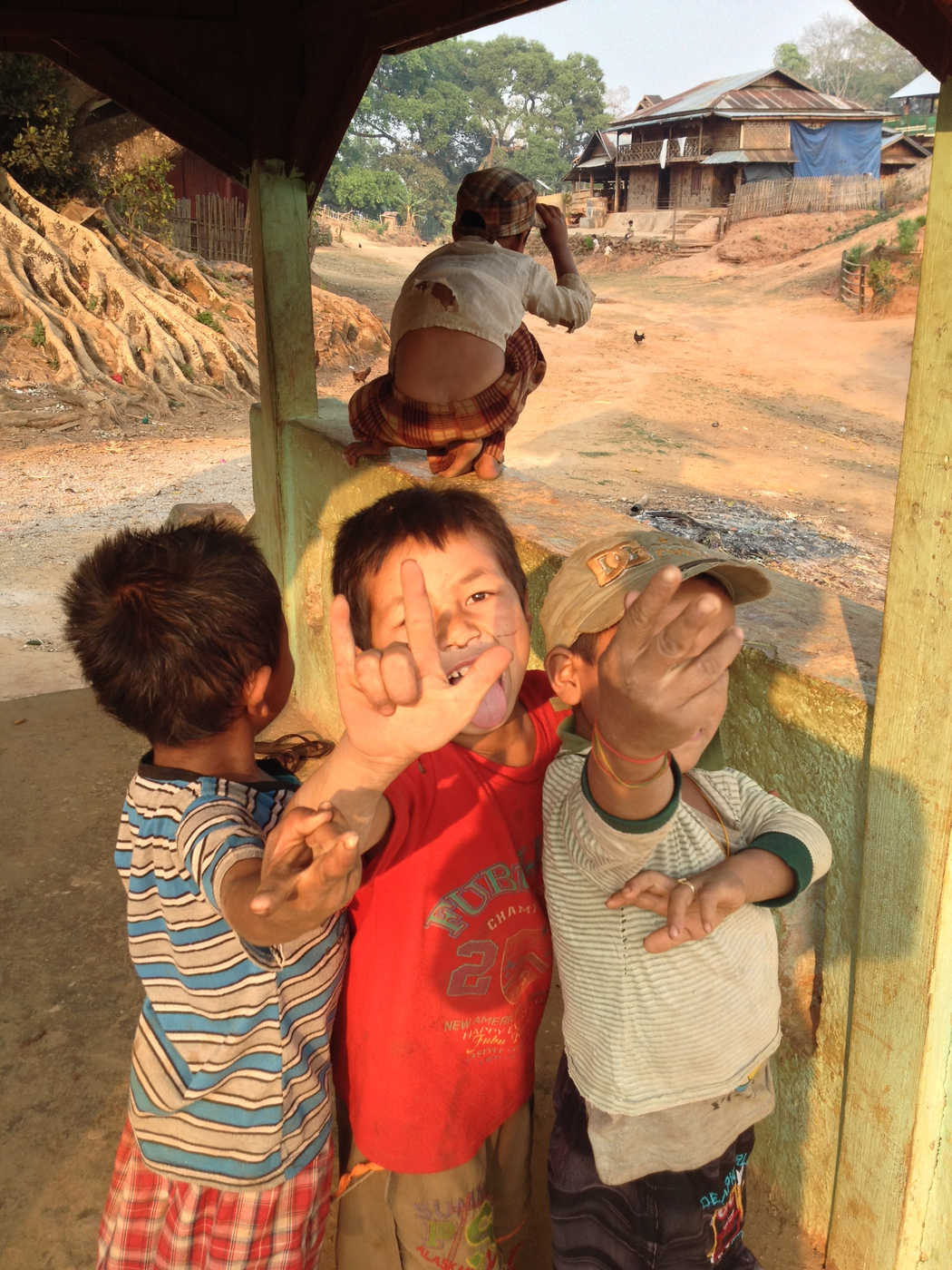

Even after the opening of Burma a few years ago and the subsequent tourist ‘boom’, foreigners are still rare here. Many of the tourist spots are primarily for Burmese, particularly the (relatively) wealthier Bamar majority. The popular attractions include the many and varied tribes of Burma and Buddhist holy sites. Westerners are always targets of curiosity.

By the way, if you want to go to Burma, go soon. As part of a series of reforms starting around 2011, Burma opened itself to almost all travelers. Already there are lodging shortages in the high season, although there was not much lodging to start—guesthouses must bribe the military to obtain expensive ‘foreigner’ licenses. Burma also opened istelf to heavy industrialization and international investment—a lot of that from the Chinese.

For much of its modern history Burma was a closed communist dictatorship like North Korea, with a dictator who was perhaps less competent and more insane. It is this dictatorship that gave the country the disputed alternate name ‘Myanmar’, named after the ethnic majority. Burma was once plugned into an economic crisis because General Ne Win, then the superstitious ruler of Burma, banned all currency and replaced it with a new series based on his favorite number 75 to celebrate his 75th birthday. Later on, he decided his favorite number was actually 90 and there followed another economic crisis and a coup d’etat. Now the Burmese prefer crisp American dollars printed after 2009, each bill carefully inspected before being accepted. Bills with ‘CB’ serial numbers are rejected because, I am told, ‘CB’ stands for ‘counterfeit bill’.

The traffic in Burma obeys the same rule as geese attempting to mate: the right of way belongs to whoever is largest and honkiest. The roads are crowded with blaring big rigs, busses, minibusses, trucks with a few or a few dozen locals sitting on the beds and clinging to the sides, these half-motorcycle half-truck jalopies, old cars from past generations, scooters, the oocasional sport bike, the occasional Jeep or Land cruiser, bicycles, pedestrians, bald monks and bald nuns and processions thereof; but the most common vehicle on the crowded, broken roads are cheap, single-cylinder shifter-scooters that daringly weave through the chaotic traffic from point A to point B, in accordance with the Pythagorean principle that the fastest path between two points is one most likely to kill you. Most cars are left-hand drive even though traffic flows on the right. Legend has it that General Ne Win was advised by a soothsayer to “move to the right”, and the generalissimo took this admonition more literally than was perhaps intended.

As a tourist you will often find yourself on the motorcycle-trucks, the preferred way to get around routes that don’t merit a van in places that don’t merit taxi service. The front half is a bike with a giant single-cylinder engine, the rear half a welded steel cabin with two or three minimal benches. It belches black smoke as the big air-cooled two stroke spins the whirling crankshaft that drives the rear wheels. You can squeeze into one of these maybe eight tourists or maybe twenty Burmese. Don’t relax your posture—the naked steel bars smack you uncomfortably as your ride bounces chiropractically over the rough dirt roads.

The landscape around the cities is visible through a haze, darkly; the further mountains rendered greyer in the distance until the grey horizon engulfs all beyond. Burma is about as polluted as you would expect from a poor area being overrun by Chinese factories and slash-and-burn farmers. Rice paddies are cleared and burned twice a year, and, due to lack of infrastructure, trash is burned all year round. The wet heat makes the smell particulalry acrid. The cities are dominated a cacophony of blaring vehicles, hawkers, shouting children, shouting adults, Buddhist cantors, pagoda bells, the occasional Muslim prayer tower, the occasional stray dog. The streets smell of food, sewage, and burning trash. The sun beats down an intense heat, delivering twice as much solar radiation as we get in America, averaging 96 degrees during hot season. Mosquitoes (carrying malaria) swim in the stifling air. Air conditioning is rare even in those guesthouses that are licensed for Westerners. Traditional food comes from pots that have been sitting out in the heat, and is served with side dishes: hot chili, various vegetables, sauteed leaves of some kind; the waiters brushing away the flies as they move them from one patron to the next. But the Burmese also like food fried to order; you might want to eat that instead.

I wanted to never leave. It is hard to say why. I don’t want to say something like “despite the inconveniences…” It is not that the good outweighed the bad. It is more that there was something in the air in Burma, even in the cities; some feeling of reality that made the bad seem not so bad, maybe even necessary, inseparable. But of course any such ‘bad was outweighed by the good, no contest.

The Burmese are deeply religious, and although their religion did not reach the architectural and cultural heights of Thailand or Cambodia; they compensate in volume, audacity and devotion.

It’s easy to immerse yourself in this country—the harsh climate and lack of comforts forces immersion upon you. The heat and light and atmosphere puts everything in Technicolor. There are no cell phones, very little Internet, no screens everywhere to distract you from where you are.

English is surprisingly common in the cities but disappears as soon as you venture out. The language barrier will not stop people, particularly children, from shouting things like “Hello bye bye!” in various permutations. Many of the homes are partially enclosed, and the Burmese are wont to hang out outdoors anyway in the hot weather.

I have not encountered a friendlier group of people. The Burmese are infalliably open, friendly, full of cheer. As in neighboring Thailand, negativity is a sin, a bad interaction a loss of face for everyone involved. Their honor is legendary—I have several stories about travelers losing things—fat wads of cash, wallets, iPhones worth six months’ farm wages—but never once heard of anything bad happening to a traveler.

There and back again

This likely concludes my travel blogging. Among the places I ended up not blogging about were Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, the Czech Republic, Serbia, Bosnia, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Singapore, Malaysia, Burma, China, and Korea, and that is a lot of places. Over time, the wonder of sightseeing gave way to the fun of experience, and traveling became mostly about living in a culture. Reflecting on these experiences in the form of a blog post seemed almost inappropriate, as though the act of reflection would take them away. In addition, I had been freelancing and keeping busy with work on the road, and these two factors made blogging less compelling, but there are some places that deserve a blog post.

Burma was a place I did not want to leave. The broken ground below you and the bright sun above, the naked simplicity and poverty, the swimming hot air, the sights and sounds and smells, the society that wants to welcome you with its best face, the traffic that wants to kill you. The cities and towns and villages of Burma are charged with reality and all your senses make you aware of it. But as a traveler you enjoy privileges these people do not enjoy. You can afford a room with air conditioning, if you need it; medical care if you are sick; a ride to wherever you want to go; unlike most desperately poor places, Burma is a safe place where nothing bad will happen because you can afford for nothing bad to happen and there are no other dangers… So here is life in a more raw state, but for us, with a safety net. The charged reality is not so real to you as those who must suffer it, for whom a mosquito bite or a fever could be a death sentence and the daily bowl of rice is no guarantee. The people here would abandon it all, they might even kill—indeed, in Burma’s history people killed for far less—for a grasp at the comfortable Western life that seemed now to me so unconvincing, like a painting of something too good to be true.

Credits

The headline picture of Bagan is in the public domain.