Suppose I told you there was a man who wanted to destroy civilization, and in his home country he did, more or less.

That sounds like something from a James Bond movie. A villain sits in his villain chair, petting his cat, cackling, “When my grand plan is complete, civilization will be destroyed and remade according to my plan, for my people.”

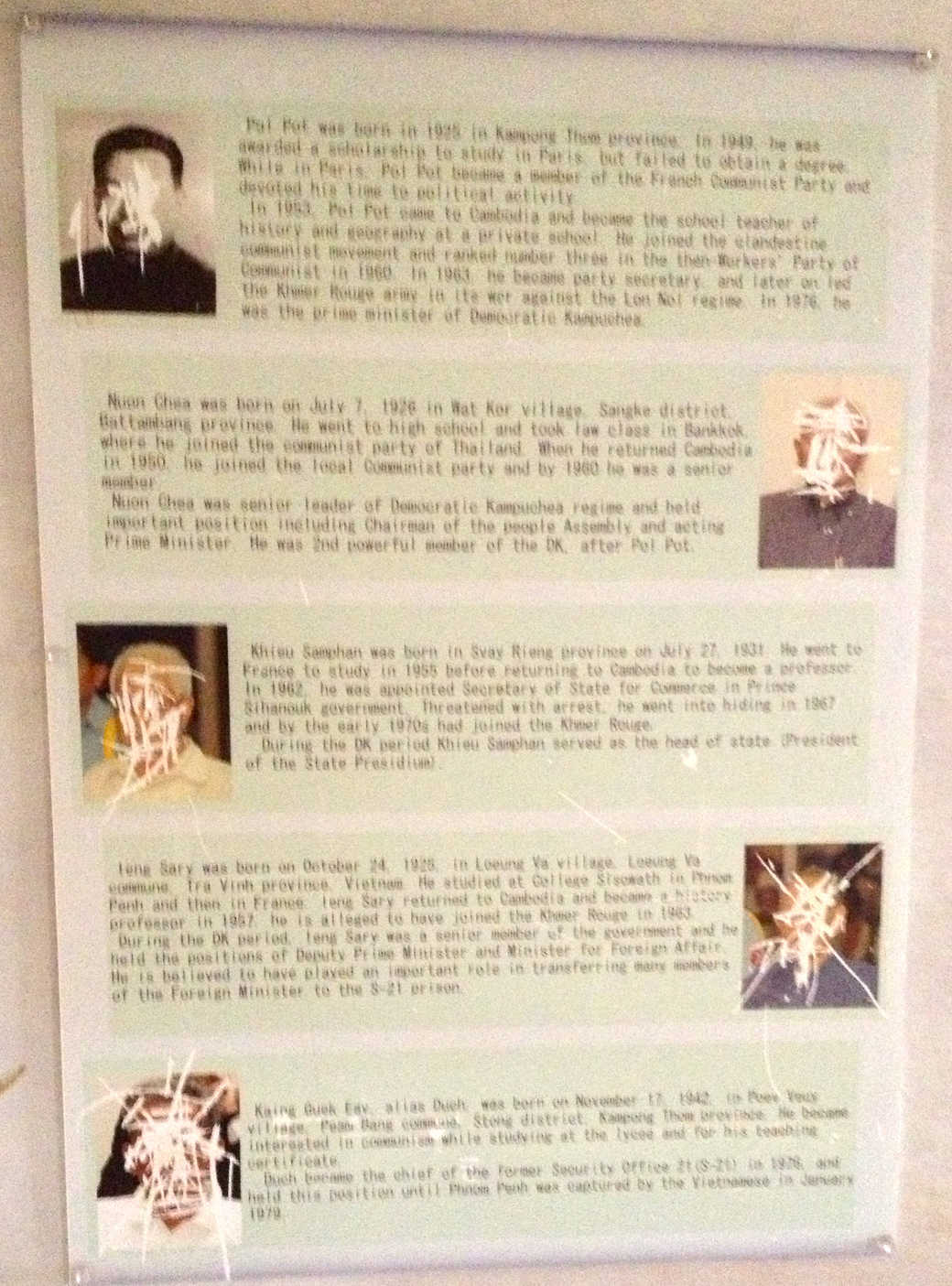

But I mean that this was actually attempted. A military group seized control of Cambodia and set to work emptying cities and eliminating entire classes and groups of people. Their leader, Pol Pot, was a man ordinary in intellect but unusual in his unbalanced paranoia; fear of of other races, other classes, and hidden forces. He struggled academically when he studied in France and fell in with Marxist anarchists before dropping out and returning to the revolution in Cambodia. He must have had some talent for leadership, because he ended up in charge, and his philosophy had sufficient appeal among the violent.

Marxists were already fighting in Cambodia when Pol Pot arrived on the scene. Marx taught that all profit was exploitation, all the bourgeoisie were profiteers, and the system was built in their interests. The exploitation of workers was encoded into society’s structure. Only a workers’ revolution, setting up the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, could ultimately be trusted with power and capital. But this is not what Pol Pot believed.

He distrusted intellectuals and felt that civilization itself was fundementally exploitative. By this point in history, it was known how the Russians had just replaced the old system of exploitation with one of their own. The pattern repeated itself throughout the Communist world and he feared it would repeat in Cambodia. There was some kind of institutional memory: the old people wanted to hang on to power and the old system tended to perpetuate itself.

When Pol Pot and the revolutionaries, the Khmer Rouge, took charge, they decided the system must be wiped out, and everyone that comprised it.

The Killing Fields of Choung Ek lie outside Phnom Penh, to the south. They are not far, but the drive through Phnom Penh’s chaotic, seething traffic make it seem much farther. It is one of three hundred killing fields that we know about.

In its time, the Rouge managed to kill about 1.5 to 2.2 million people, depending on who you ask. There were only 7 or 8 million people in the entire country.

The mood at the Killing Fields is somber, still and silent. Most here are foreigners. People don’t talk or make eye contact very much. They wander through like ghosts in a graveyard, listening to electronic guide devices that speak only to them.

In addition to all the foreigners, there are some Khmer visitors.

There is a marsh on the field grounds if you want to get away from the skulls—but this is no guarantee, as rain and pedestrian traffic naturally unearths new bones all the time.

The purpose of all this killing was something called “Year Zero”. The old society would be destroyed, and a new Khmer-only agrarian paradise put in its place. The past and its memory and legacy would be eradicated. There would be no history before Year Zero.

The “Old People” of the old society were eliminated, either directly, or by reeducation via forced labor. “To keep you is no gain,” they were told, “to destroy you is no loss.” These Old People were anyone connected with the class system that exploited farmers. This included all city dwellers, bureaucrats, capitalists, supporters of the old regime, the wealthy, the well-educated, intellectuals, and schoolteachers. They also killed Christians, Muslims, active Buddhists, Thai, Vietnamese, Chinese, other foreigners, and anyone else they didn’t like. Rouge cadres would cross the Vietnam border for no other reason than to massacre villages of Vietnamese. Cities were emptied for the most part, with only a few cities like Phnom Penh retaining a small core governmental seat.

The Rouge took charge of the economy. Southeast Asia supports two rice harvests a year. They demanded three harvests, then four. Those who didn’t make quota were class traitors.

At the S-21 prison in central Phnom Penh you can read the confessions of those they tortured. Some prisoners would weave outlandish stories about how they worked for the CIA or the fascists or the Viet Cong, throwing in details about drugs, women, dishonesty and other sins. Other prisoners were only farmers, tortured into implicating other farmers.

This revolution, like many bloodthirsty revolutions, began with Marx. Such revolutionaries believed in Marxism like a religion, but they called it a science. They felt they understood the gears of the world, and could ultimately control them. It was considered proven that the revolution would come, and they would be at its vanguard. Pol Pot arguably fell away from Marxism, or perhaps just cut to its revolutionary core, throwing out the intellectual pretense but retaining the burning moral purpose and sense of inevitability.

The Rouge taught that Cambodia belonged to the Khmer farmer and him alone. The history of Cambodia was of class oppressing class and race oppressing race, with the Khmer usually on the losing end; throughout the centuries variously exploited by foreign invaders, colonialists, and their own people; starving as they farmed so others could feast. It is easy to see how this idea had appeal.

Like any good religion, Marxism (including Pol Pot’s version) has its own eschatology: the so-called end of history, the Communist paradise where there would be no power, no want, no suffering, no exploitation, not even the command structure of society; all people living in self-organized harmony. Pol Pot said, yes, this could happen in your lifetime, once you drive out all the exploiters and the system of exploitation. If you thought you were bringing about paradise on Earth, isn’t that worth fighting for? Isn’t that worth dying for?

Isn’t that worth other people dying for?

The Rouge lasted three years before Vietnam invaded with the intent of deposing the regime. They took Phnom Penh in seventeen days.

It’s said that 75% of Cambodia is too young to remember the Rouge, partly because so many of the old generation were killed. But some visitors to S-21 let it be known what they thought of the Rouge leaders.

I bet a lot of people go to these places because they feel they should, become sad for a while, and then go on. Floating through the Phnom Penh death museum circuit then wandering on to Angkor or a beach resort in Sihanoukville. My tuk-tuk driver seemed a little cynical about the whole thing. “Your country kill people too, right?” he asked as I returned from S-21. “America kill too, right?” I didn’t have a good response.

But it is good to see these places and get, at least, a deeper impression and knowledge of the shallow moral clarity by which man forsakes man and the eagerness with which people jump to violence. The story of Red Cambodia is not the only such story, nor the most exemplary, but it is fair to rank it among the most brutal in recent memory.

I’m drafting this post on an airplane, going back home to America. I didn’t get the first-class upgrade I wanted, but I did get an extra legroom seat. On an in-flight video, Jimmy Kimmel is directing blindfolded karate masters to attempt to kick open a rotating set of piñatas. The blind martial artists kick around in circles like epileptic Rockettes while the audience laughs uproariously. We surround ourselves with frivolity and luxury, and our home part of the world has not, in living memory, really suffered.